You know how security people get all uppity about SSL this and SSL

that? Stuff like posting creds over HTTPS isn’t enough, you have to load

login forms over HTTPS as well and then you can’t send auth cookies

over HTTP because they’ll get sniffed and sessions hijacked and so on

and so forth. This is all pretty much security people rhetoric designed

to instil fear but without a whole lot of practical basis, right?

That’s

an easy assumption to make because it’s hard to observe the risk of

insufficient transport layer protection being exploited, at least

compared to something like XSS or SQL injection. But it turns out that

exploiting unprotected network traffic can actually be extremely simple,

you just need to have the right gear. Say hello to my little friend:

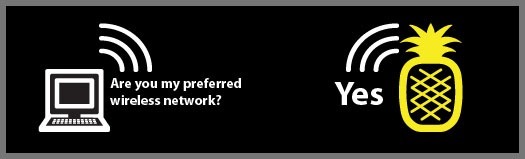

This, quite clearly, is a Pineapple. But it’s not just any pineapple, it’s a

Wi-Fi Pineapple

and it has some very impressive party tricks that will help the

naysayers understand the real risk of insufficient transport layer

protection in web applications which, hopefully, will ultimately help

them build safer sites. Let me demonstrate.

What is this “Pineapple” you speak of?!

What

you’re looking at in the image above is a little device about the size

of a cigarette packet running a piece of firmware known as “Jasager”

(which over in Germany means “The Yes Man”) based on

OpenWrt

(think of it as Linux for embedded devices). Selling for only $100, it

packs Wi-Fi capabilities, a USB jack, a couple of RJ45 Ethernet

connectors and implements a kernal mode wireless feature known as

“Karma”.

Huh? This is starting to slip into the realm of

specialist security gear which is increasingly far away from the

everyday issues we deal with as software developers. But it’s

exceptionally important

because it helps us understand in very graphic terms what the risk of

insufficient transport layer protection really is.

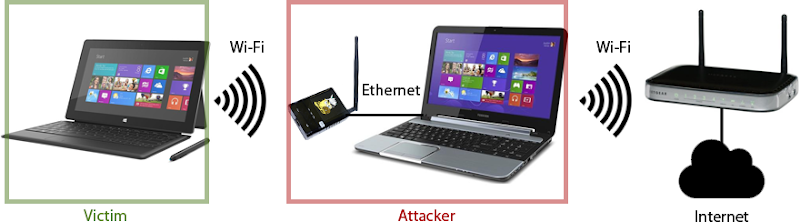

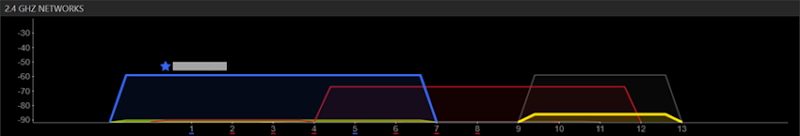

The easiest

way to think of the Pineapple is as a little device that sits between an

unsuspecting user’s PC (or iPhone or other internet connected device)

and the resource they’re attempting to access. What this means is that

an attacker is able to launch a “Man in the Middle” or MiTM attack by

inspecting the data that flow between the victim and any resources

they’re accessing on the web. The physical design of the Pineapple means

that victims can connect to it via its Wi-Fi adapter and it can connect

to a PC with an internet connection via the physical Ethernet adapter.

It all looks a bit like this:

This

isn’t the only way of configuring the thing, but being tethered to the

attacker’s PC is the easiest way of understanding how it works. The

point of all this is that it helps tremendously in understanding the

risk of insufficient transport layer protection because ultimately, it’s

websites that don’t do a good enough job of this that put the victim at

risk. More on that later.

But why on earth would a victim

connect to the Pineapple in the first place?! Well firstly, we’ve become

alarmingly accustomed to connecting to random wireless access points

whilst we’re out and about. When the average person is at the airport

waiting for a flight and sees an SSID named “Free Airport Wi-Fi”, what

are they going to do? Assume it’s an attacker’s honeypot and stay away

from it or believe that it’s free airport Wi-Fi and dive right in?

Exactly.

But of course that’s still a very conscious decision on

behalf of the user. As it turns out, the Pineapple packs a much more

subversive party trick to lure unsuspecting victims in…

Karma, baby

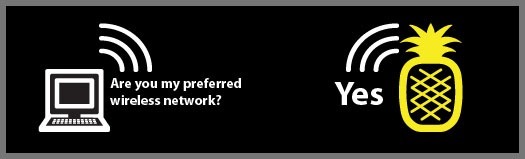

The Karma feature is best explained on the Pineapple website:

Most

wireless devices including laptops, tablets and smartphones have

network software that automatically connects to access points they

remember. This convenient feature is what gets you online without effort

when you turn on your computer at home, the office, coffee shops or

airports you frequent. Simply put, when your computer turns on, the

wireless radio sends out probe requests. These requests say "Is

such-and-such wireless network around?" The WiFi Pineapple Mark IV,

powered by Jasager -- German for "The Yes Man" -- replies to these

requests to say "Sure, I'm such-and-such wireless access point - let's

get you online!"

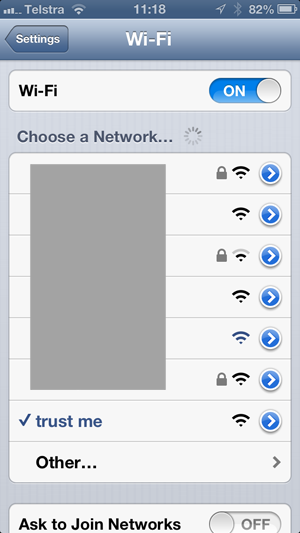

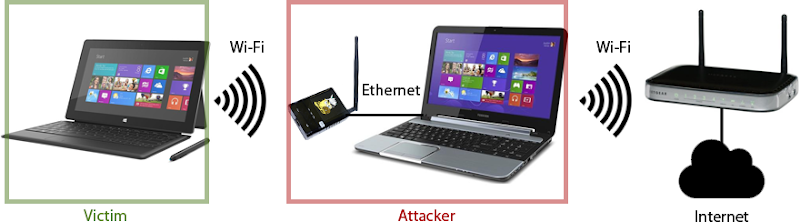

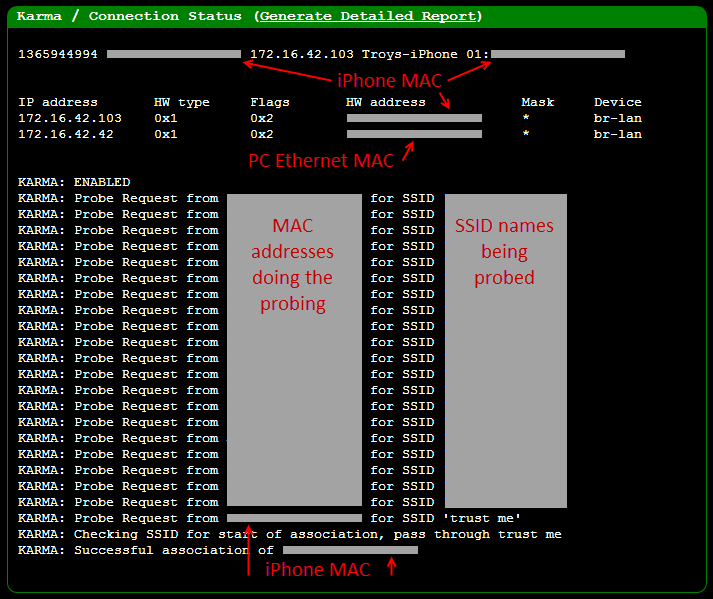

Wait, what?! So devices just randomly connect to the Pineapple thinking it’s a legitimate AP? Yep, here it is in detail:

Simple,

huh? The problem is that wireless devices are just too damn trusting.

Once they establish a connection with an access point they

usually

happily reconnect to it at a later date. Of course if it’s a protected

network they still need to have the right wireless credentials, but if

it’s an open network then the Pineapple asks for no such thing, it just

lets the device straight in whether the device

thinks it’s connecting to a legitimate access point or not.

So

that’s how she works, a combination of simply providing an access point

that victims connect to on their own free will or being tricked into

connecting via Karma. Let’s get it setup and see it all in action.

Windows tethering

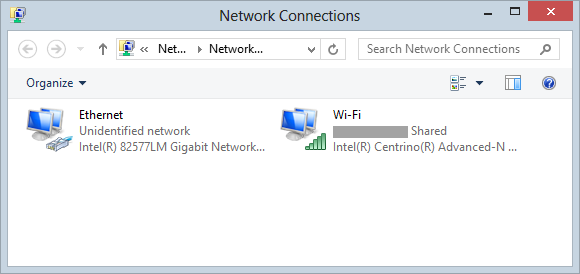

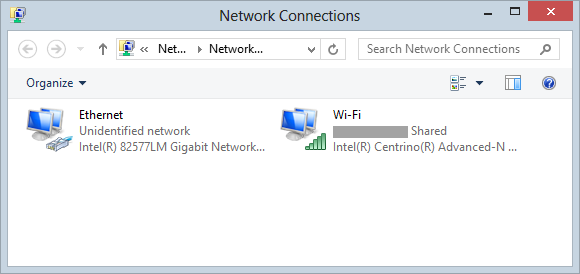

The

easiest way to access the device and get started with configuring

everything is to tether it to a PC with two network interfaces. This can

be one with a couple of NICs connected to Ethernet or in most cases

(and as with the diagram above), a laptop which commonly has a wired NIC

and a wireless one.

What we’re going to do is

configure the wired Ethernet NIC which we’ll plug the Pineapple into

then share the connection on the wireless adapter so that the traffic

from the Pineapple can be routed through it, effectively just passing

everything through the PC. This is all pretty straight forward and it

starts out from the Network Connections settings:

Just

one little note before proceeding: I’m going to obfuscate any SSIDs or

MAC addresses used in this post with a grey box simply because they

explicitly tie back to my devices (or my neighbours’ devices!) and I’m

not real keen on publicly identifying them. Who knows what they might

get up to in future…

Jump into the properties of the wireless

adapter, and head over to the sharing tab then make sure that “Allow

other network users to connect through this computer’s Internet

connection” is checked:

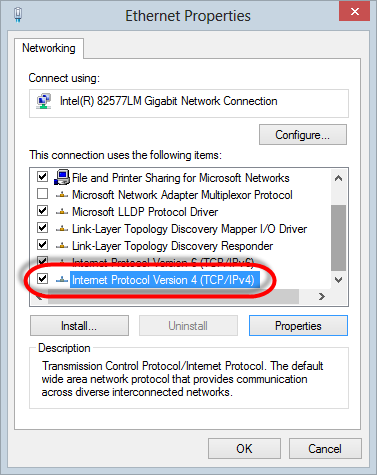

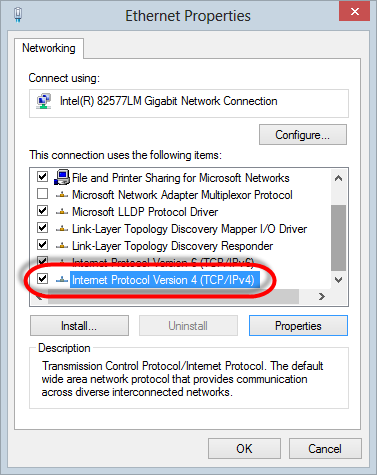

That’s

that adapter done, now let’s do the wired one. Jump into the properties

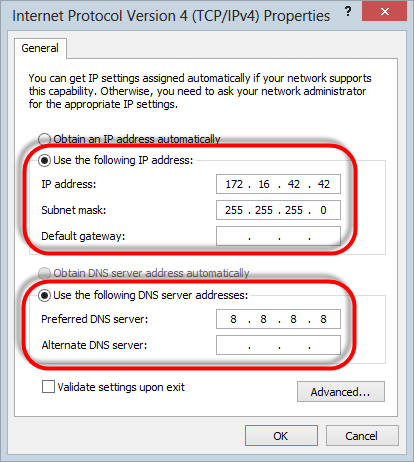

locate the “Internet Protocol Version 4 (TCP/IPv4)” item:

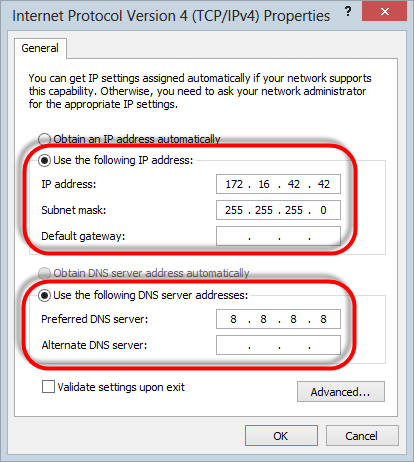

Now grab the properties of that guy and configure a static IP address and subnet mask

and set the DNS server as follows:

That’s it – job done.

Accessing the device

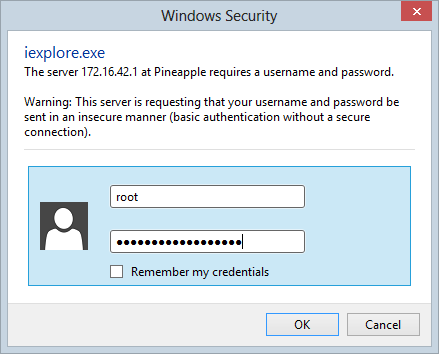

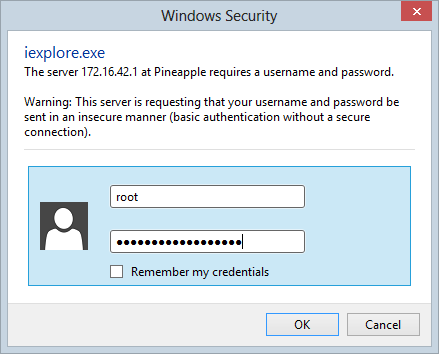

Once

tethering is setup and the Pineapple is connected to Ethernet via its

PoE LAN port, you should be able to access the Pineapple directly from

within your browser via the IP address. You can hit it on

172.16.42.1/pineapple or if running a newer version of the firmware (more on that later), the IP address and port

172.16.42.1:1471. All things going well, you’ll be challenged to authenticate:

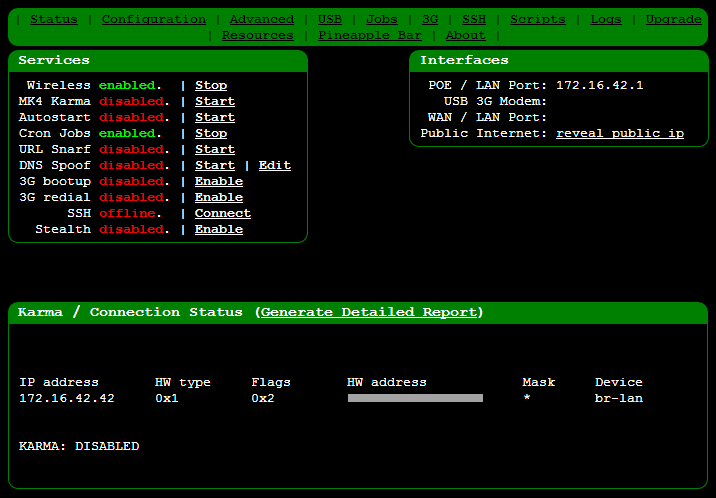

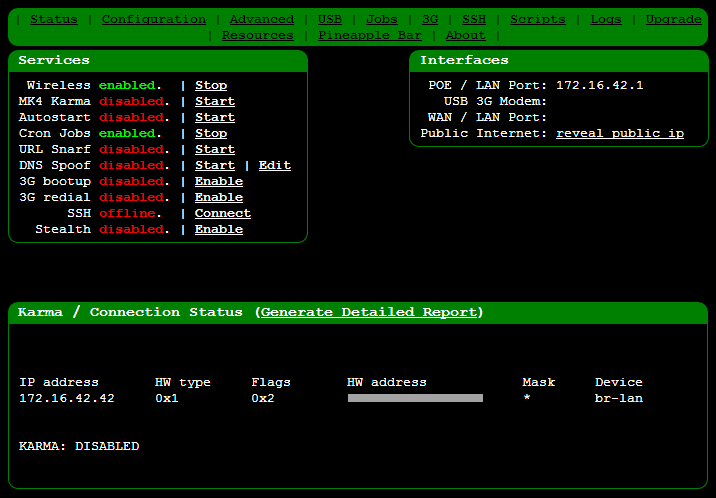

The default credentials are username “root” and password “pineapplesareyummy” after which you should be in:

That’s the first bit done, tethering is working and we can actually access the device, now for a bit of preparation.

Housekeeping

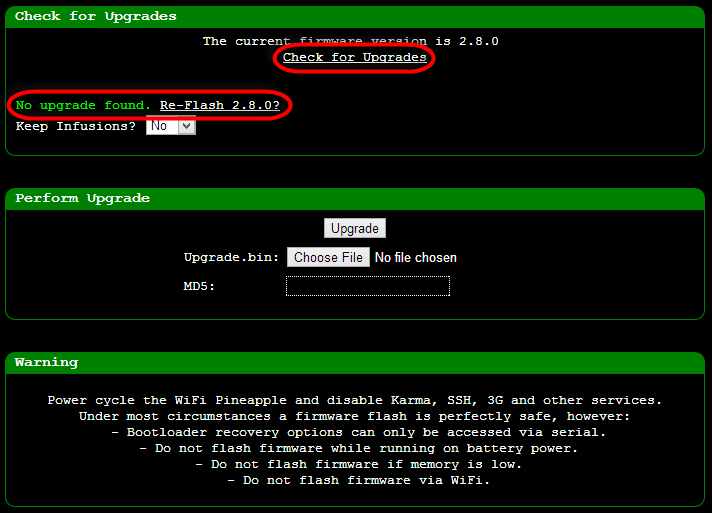

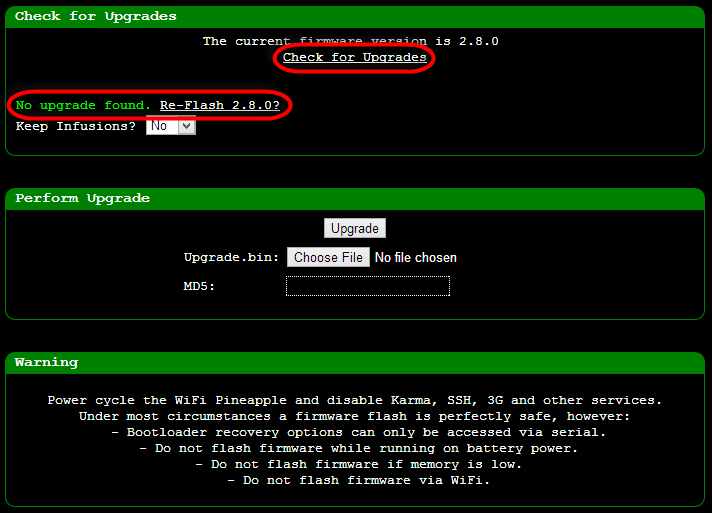

Before

you start anything, get the firmware up to date. If I’m honest, I’m

always scared about updating any firmware on any device because when it

goes wrong it’s often a whole world of pain to get yourself back out of

trouble again. You’re much better off doing this before you create any

dependencies on the device or configure anything. I had a couple of

glitches doing mine and it took a few goes, but in theory, you jump over

to the “Upgrade” link on the nav, hit “Check for Upgrades” then if

required, pull down a package, enter the MD5 hash of it (provided on the

upgrade site) and upload the package:

One little thing you want to remember here: if like me, your GUI was originally accessed via

172.16.42.1/pineapple, keep in mind the newer version of the firmware now puts the GUI behind a port so you want to hit

172.16.42.1:1471

instead. If, also like me, you try hitting the old address after the

install and reboot you’ll keep getting redirected and not much will

happen. Then you’ll think you’ve rooted your device (that’s the

Australian rooted,

not the American one) and start wondering how in the hell you’re ever

going to get it back to a known good state and, well, just remember the

port change!

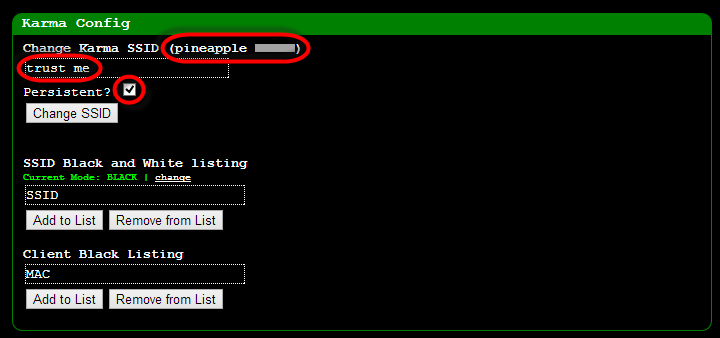

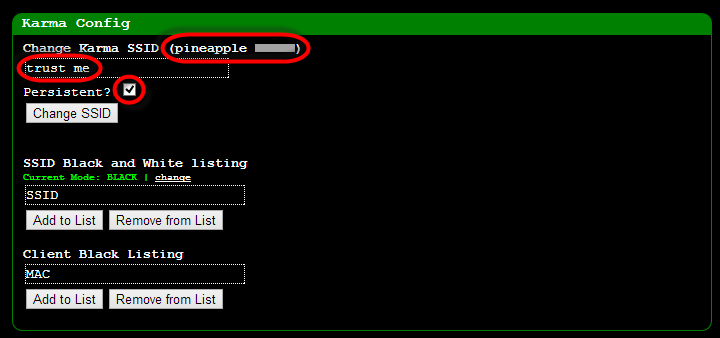

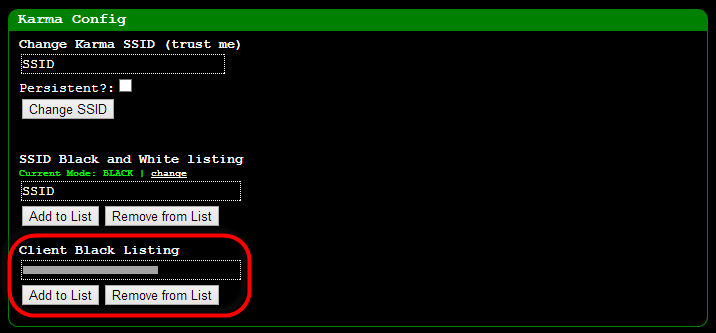

Next up, jump into configuration and change the

default SSID. The device is configured to show “pineapple” followed by

the first and last octets of the Wi-Fi adapter. Change it to something a

little more subtle and make it persistent so that when you fire it back

up later you’re not reverting to the default:

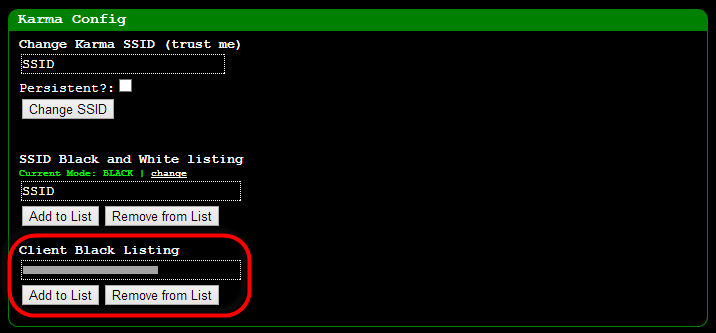

The

other thing you want to do on the configuration page is to blacklist

the MAC address of the machine you’re going to be orchestrating the

Pineapple from

and any other devices you don’t want inadvertently connecting to it.

This is important if you don’t want to “Pineapple yourself”! Seriously

though, it can get very confusing otherwise so this makes good sense.

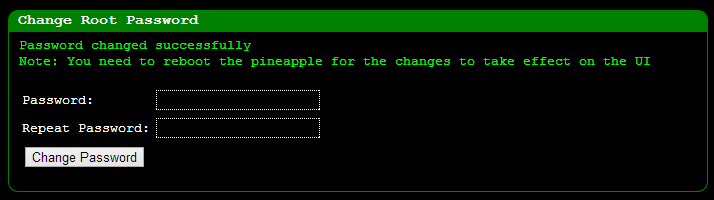

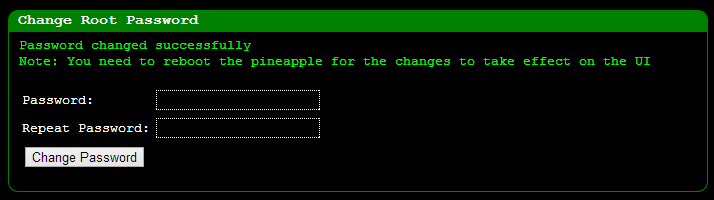

Lastly,

let’s change that default password, the last thing you want is someone

else taking over your Pineapple whilst you’re pretending to be a l33t

hax0r! Over to the “Advanced” link then down to the bottom of the page:

That’s

pretty much it for what I felt need to be configured via the UI, let’s

go and get a bit low-level and enter the command shell.

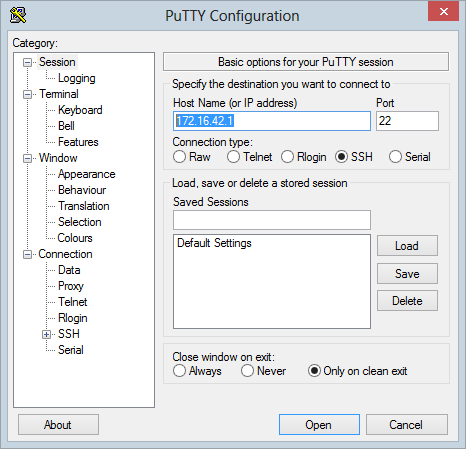

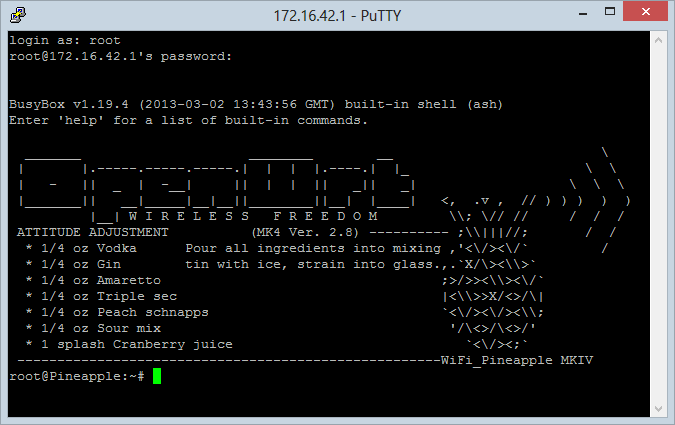

SSH’ing in

This

is where it gets a bit scary for Windows people! Keeping in mind that

the Pineapple is ultimately just a little Linux box with some fancy

party tricks, there are times when you’ll need to get your hands dirty

and enter the

secure shell

world. This is something I do very, very rarely and if memory serves me

correctly, it was 1999 when I last regularly used a *nix machine so it

was pretty unfamiliar territory for me as well.

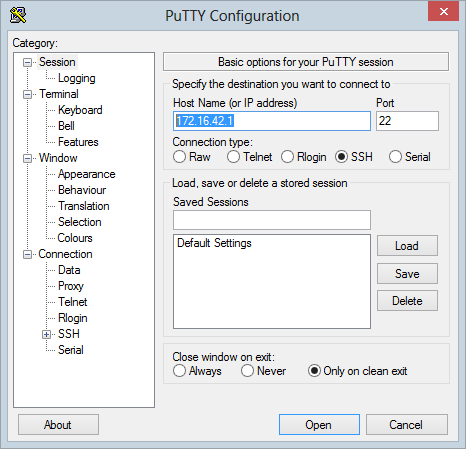

Moving on, one of the easiest way of SSH’ing into the device from Windows is to go and grab

PuTTY. With this in hand, the only configuration you need is the IP address of the device:

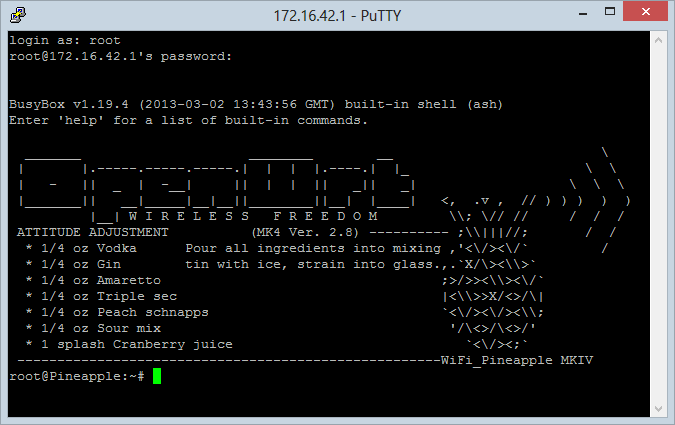

Open the connection and you’re into the shell:

Follow the instructions in the screen above enough times and suddenly the shell doesn’t seem to look so bad!

Keep

in mind that this is the OpenWrt distro of Linux and being intended for

embedded devices, it’s a pretty lean edition. Don’t expect to find all

the features you’d normally see in a full blown desktop edition – many

of them are not there so keep that in mind when attempting to use

commands that might not be supported.

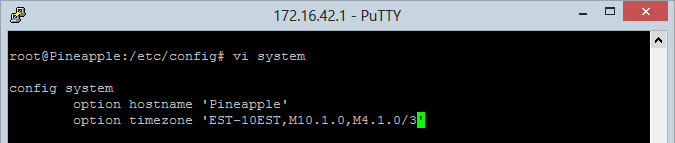

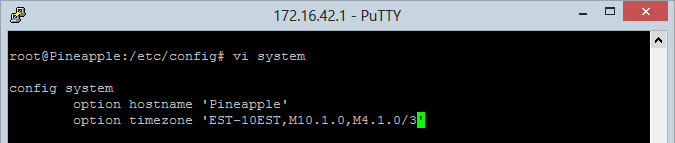

Once you’re SSH’d in you

can go ahead and set the time and time zone correctly. This’ll be well

outside your comfort zone if Linux shells are a bit foreign to you (and

admittedly I had to look much of this up again), so here’s the whole

thing step-by-step:

- Change the directory to /etc/config: cd /etc/config

- Edit the config file in vi: vi config

- Navigate

down to the “option timezone” line and delete out the existing “UTC”

value (unless, of course, you are in the UTC time zone!)

- Jump over to the timezones table on the OpenWrt site and find the appropriate one for your location.

- Enter the value from the “TZ string” column into the shell: Hit the “i” key to insert then type away

It should look kinda like this when you’re done:

- Save the file: Hit the esc key to stop editing then :wq<enter>

- Reboot the Pineapple: reboot <enter>

A

little tip for new players: every time I tried saving the config change

I got the following message and nothing actually saved:

This,

quite clearly, means that there is no available capacity on the device

and after wasting considerable time trying to work out why I couldn’t

use vi correctly, this become quite clear. Welcome to Linux!

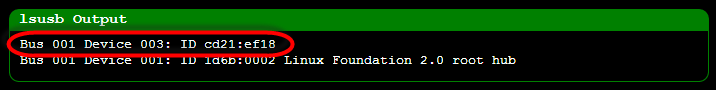

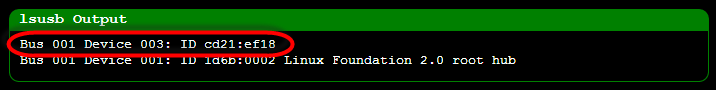

Working with ext4 format and USB drives

You’ve got

very

little space on the device, there’s literally only an 8MB ROM and 32MB

of RAM so by the time you load everything into there just required for

the device to run, there’ve not much left. It’s

certainly not going to be enough to start doing fancy things like storing packet captures which mount up very quickly.

Fortunately

it’s all expandable via USB so one of the first things you want to do

is grab a spare thumb drive and get it ready for the Pineapple. But

there’s a catch – as with many things Linux, this is a slightly

different world to good old Windows so you can’t just take your NTFS

formatted USB stick and chuck it in, you’ll need to partition it for

ext4.

In theory, this is easy enough to do in the Windows world using a tool such as

MiniTool Partition Wizard.

That sounds just fine – except it’s not and you will only discover this

through either banging your head against the wall for hours or reading

what comes next. Whilst the aforementioned tool (and I assume others

like it running on Windows)

seemed like a good idea, I just couldn’t get it to play nice. I’ll spare you the detail as

I’ve captured them all on the Hak5 forum,

but in short, the USB would mount and be readable from shell but I

could never install Infusions to it (think of them as apps for the

Pineapple) which I’ll come to shortly. It turns out that additional

partitions were being created and that simply made things not play nice

with the Pineapple despite no obvious warnings to that effect.

The

solution turns out to be that I needed to create the ext4 partition

directly from a Linux machine. If this world is unfamiliar to you,

there’s a (relatively) low friction process courtesy of an

Ubuntu LiveCD.

This involves downloading an Ubuntu ISO, burning it to CD (or DVD or

bootable USB), running up an in-memory instance of Ubuntu and

partitioning the USB from there. I then followed the guidance provided

in the very easy to follow page on

enabling USB mass storage with swap partition

as the swap partition looks like will come in handy later on when you

want to start doing some other tricks with the Pineapple.

That

sounds like a hassle – running up an entire new operating system just to

partition a USB drive – and certainly it was a drama getting to the

point of realising that’s what I needed to do, but once you know what

needs to be done it’s quite simple. Of course it would have been even

simpler if I had a handy Linux machine hanging around somewhere and for

many people, that will already be the case.

Once it’s all setup you should see the storage appear under the “USB” menu item like so:

You’ll also probably want to

read from the drive back on your Windows machine at some point (I’ll save some packet captures to it a little later on) and I found

DiskInternals Linux Reader did the job just fine.

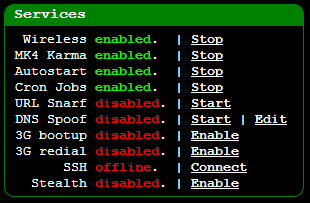

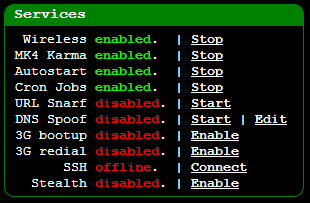

Testing connectivity

Now

that we’ve got everything ready to roll, let’s jump into the fun stuff!

Back in that first screen grab of the UI, only the “Wireless” and “Cron

Jobs” services were running so let’s fire up “Mk4 Karma” and set it to

run automatically via the “Autostart” feature so the device just needs

to be powered up for everything to kick into action:

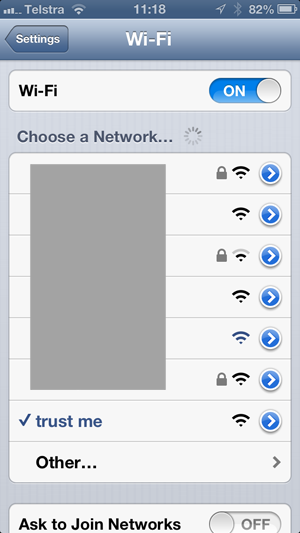

Now we should be able to jump over to a device such as my iPhone and see some new SSIDs:

This

is a whole lot more interesting once you understand what’s under the

grey box (which again, I’ve deliberately obfuscated), so let me explain

what’s happening; each unsecured network is the Pineapple responding to a

probe request from the iPhone with the name of the SSID it was

previously associated with. The names include that of an old wireless

router I replaced some years back, my parents’ network I was connected

to interstate just the other day and an airline lounge in a far flung

corner of the world. All of the

secured networks are legitimate (mine, my neighbour’s, etc.)

We’re

also seeing the new SSID of the Pineapple that I set earlier (“trust

me”) and I’ve gone ahead and explicitly connected to that for

demonstration purposes. This now makes the homepage of the GUI much more

interesting:

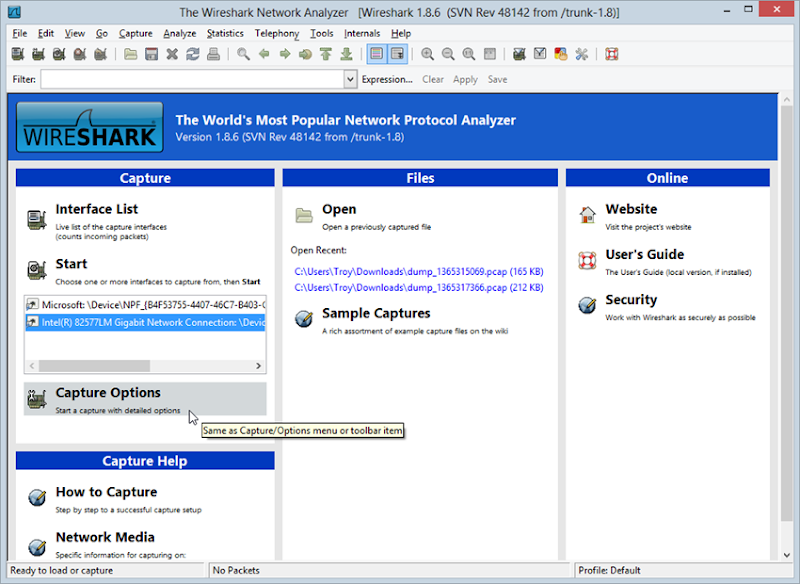

What’s particularly interesting is what you

can’t

see which are all the SSIDs being probed for. These are predominantly

APs I’ve connected to in the past and the MAC addresses doing the

probing are predominantly my own (the Wi-Fi strength on the Pineapple is

not great so I’m seeing mostly nearby devices), but you do see a few

unfamiliar ones pop up which are clearly other people’s devices. It does

make you wonder what risks might be present from devices leaking SSID

names they’ve previously associated to; “Why is my colleague’s Android

trying to connect to ‘Mistress Angeliques BDSM Palace’?!”

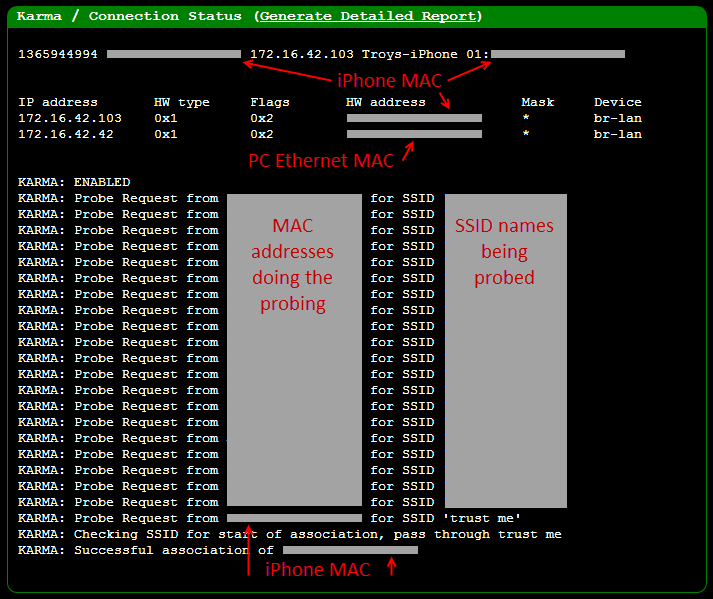

Anyway,

right at the end of the above image you can see the association of my

iPhone to the Pineapple which means we can now drill down and get a

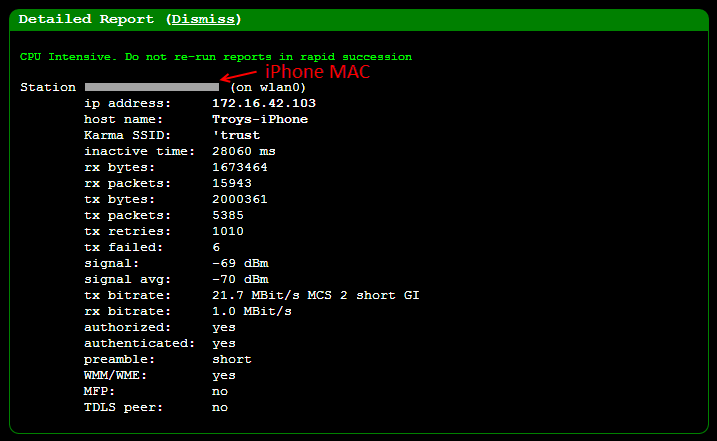

detailed report of what’s going on:

This

is mostly self-explanatory, the signal strength is kind of interesting

as it starts to give you a sense of the distance the victim might be

from the device. Of course what will be really interesting is the rx

bytes – that’s about one a half MB that the phone has already received

through the Pineapple and under normal operating conditions, the user

would have absolutely no idea there was an MiTM. Let’s move on to taking

a sneaky look at those packets because that’s where things get

really interesting!

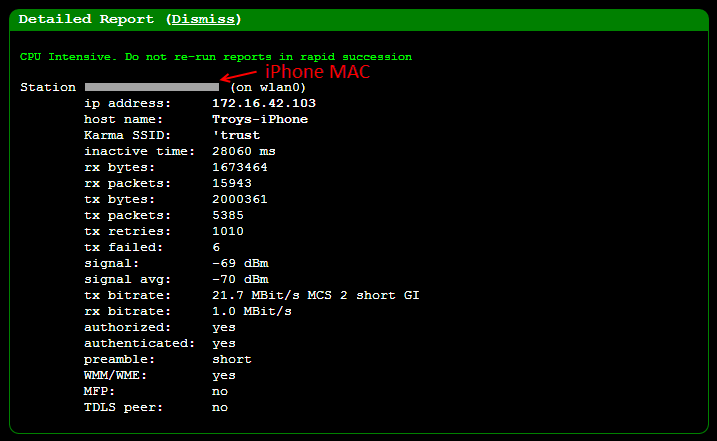

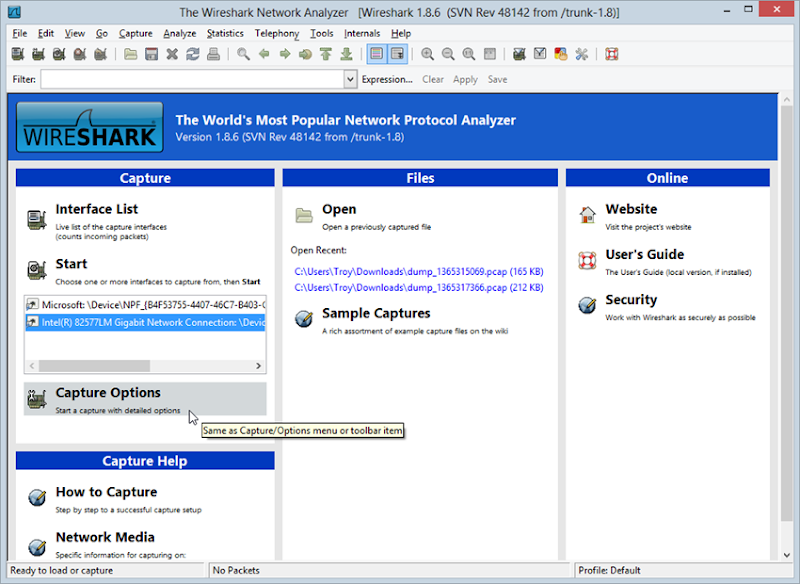

Packet capturing

Now

that we’ve got all the nuts and bolts in place, let’s start capturing

the data. There are a couple of different ways of doing this and

probably the simplest is to monitor the traffic moving through the

Ethernet adapter on the attacker’s PC. Once we start getting into the

realm of traffic monitoring we need to start looking at packets and the

best way to do this on a PC by a long shot is to use

Wireshark.

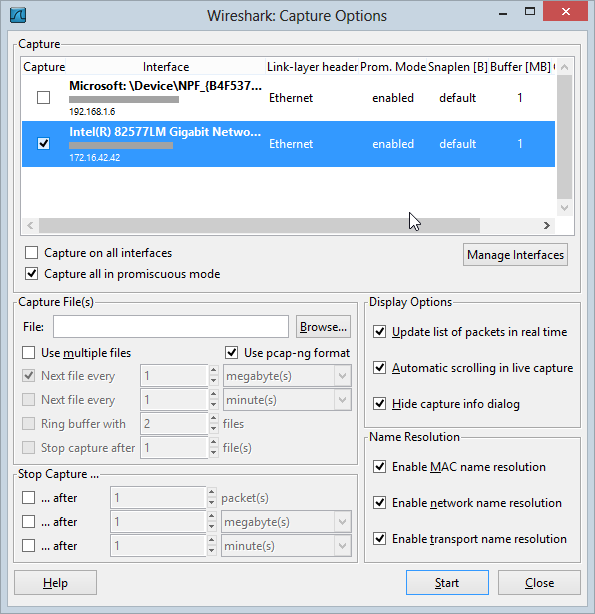

One

of the best thing about Wireshark is that it’s free. This is no

lightweight tool either, Wireshark is very full featured and is arguably

the de facto standard for monitoring, capturing and analysing packets

flying around a network. As powerful as Wireshark is, it’s also

relatively easy to get started, just fire it up, choose the network

interface you want to capture which in this case is the Ethernet adaptor

(remember, this is the NIC the Pineapple is connected to) then jump

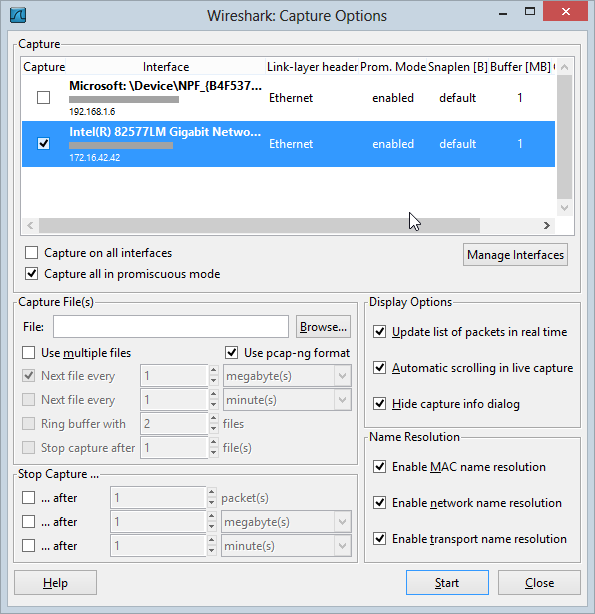

down to the “Capture Options” button:

The

capture options start to give you an idea of the extent of the

configurability but we’ll just leave all that as default and start the

capture:

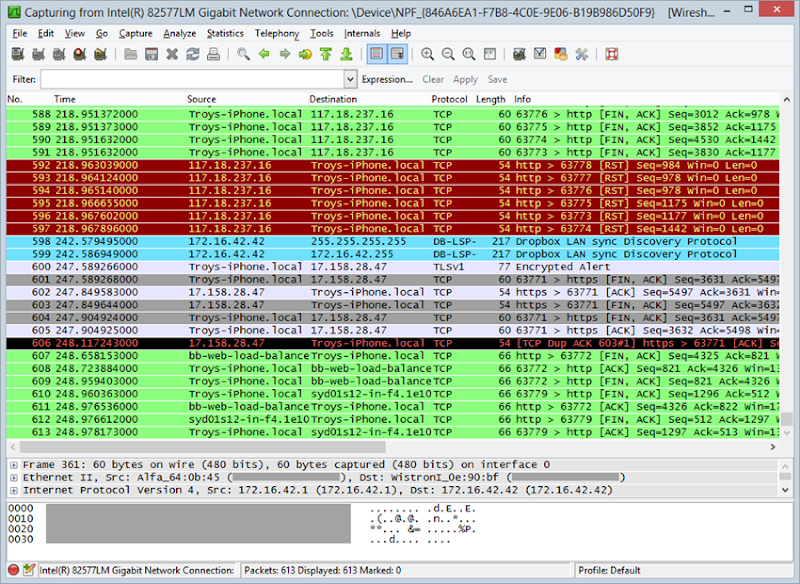

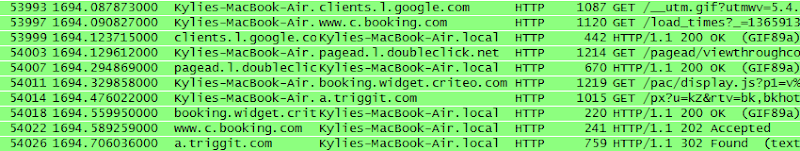

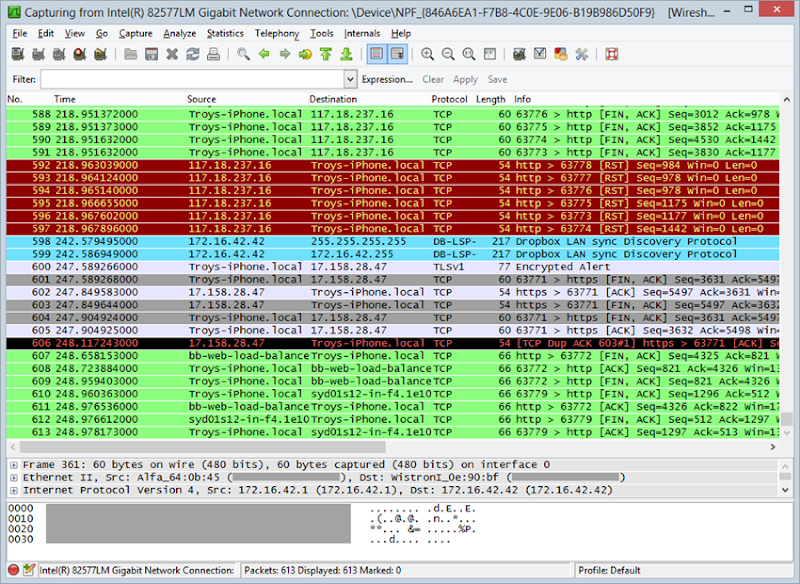

Once started, you should immediately begin to see packets flowing through the NIC:

Right about here the penny should drop –

this is someone else’s traffic!

Ok, it’s really my own traffic from my iPhone but of course as we now

know, the Pineapple has the ability to easily trick a victim into

connecting to it whether deliberately or by default as their device

looks for familiar SSIDs. Long story short is that this could just as

easily be someone else’s traffic.

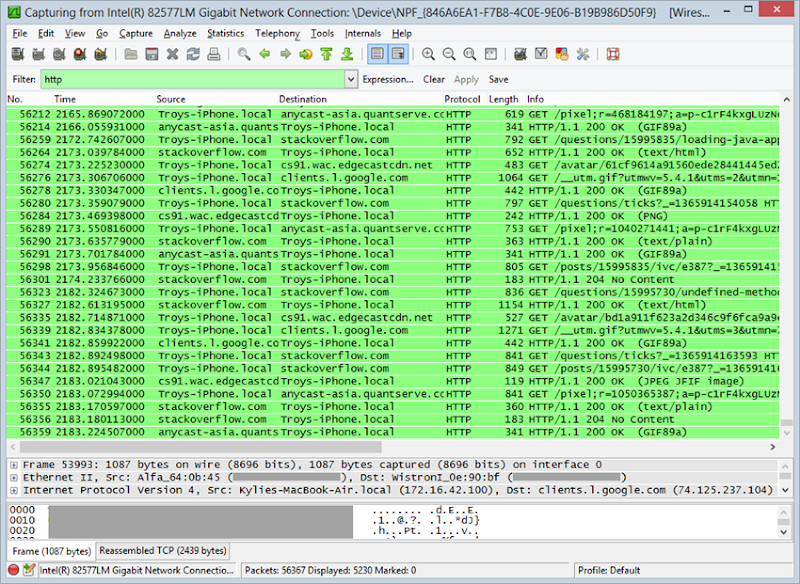

I’m not going to delve into

exactly what we can do with that traffic right now because I have

subsequent posts planned that will demonstrate that, for now though

let’s just filter that traffic down to something a bit more familiar –

HTTP. You see, the traffic above includes a whole bunch of different

protocols which for the purposes of talking about secure website design

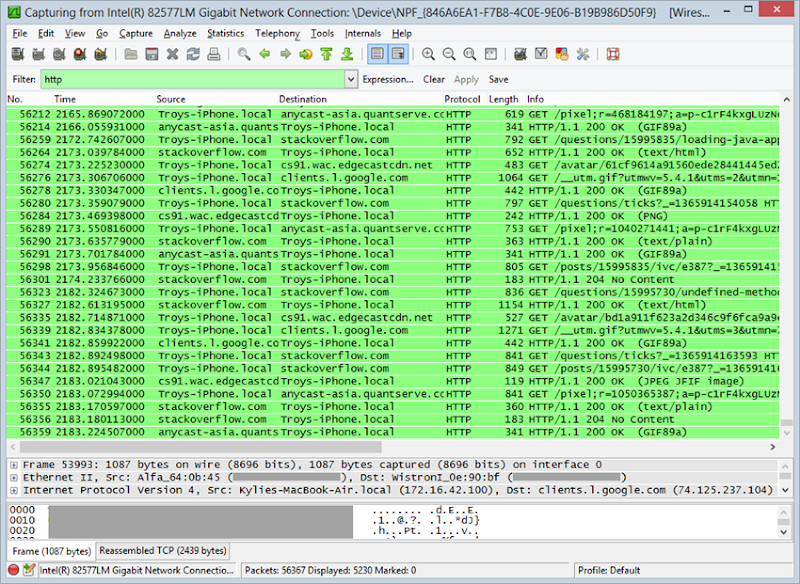

aren’t going to be of much use. Let’s add in a filter of “http” and load

up a popular website with developers:

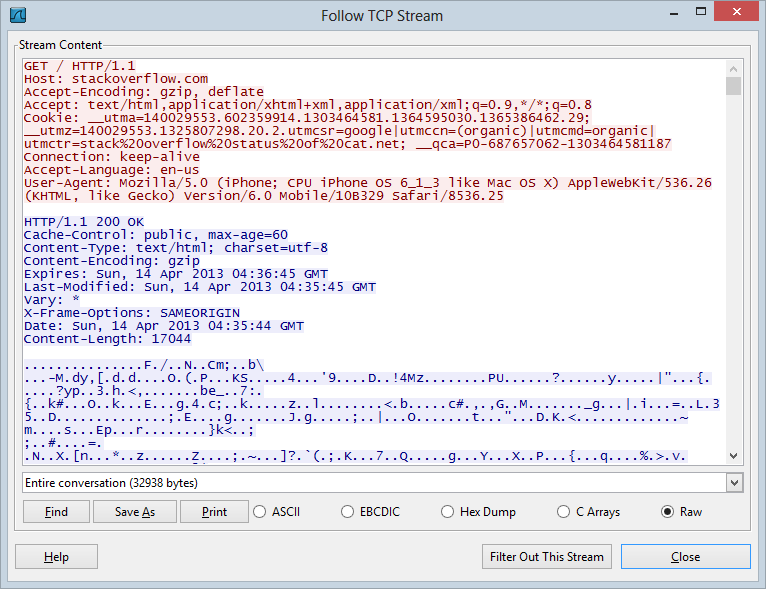

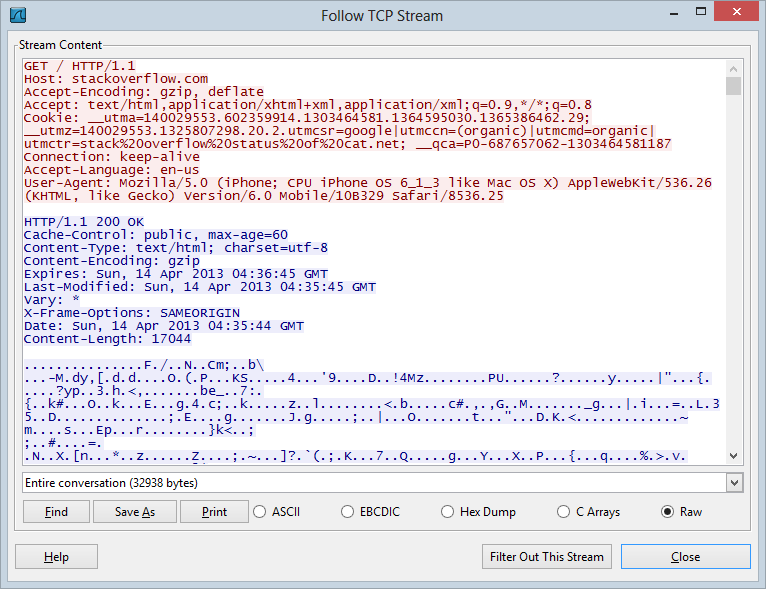

As I’ve written before,

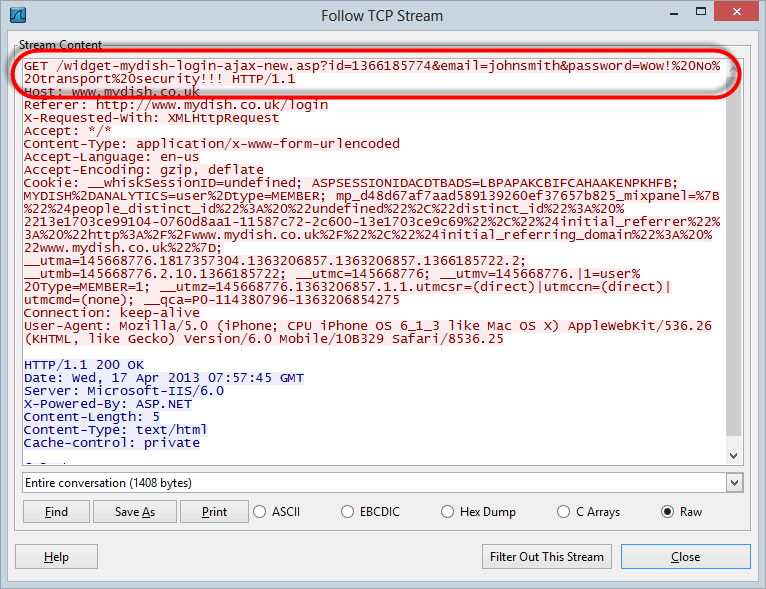

Stack Overflow serves everything outside the logon over HTTP

so it’s easy to monitor that traffic (including the authentication

cookie). Once the traffic is captured, you can either save it as a PCAP

file for later analysis or right click and follow the TCP stream which

then gets you into the entire request and response (including the

headers with those valuable auth cookies):

I’ll

stop there because that’s enough to demonstrate that everything is

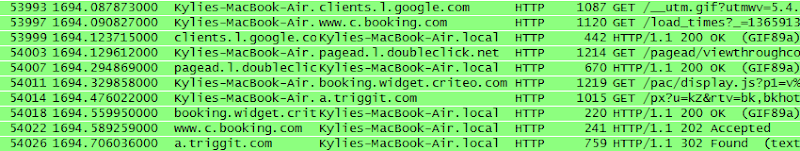

working as expected. Just to illustrate the power of the Pineapple, as I

was writing this piece and watching the Wireshark traffic, a whole

bunch of packets started appearing

that weren’t mine:

Turns

out that my wife had wandered into range with her MacBook Air and it

had automatically associated to the SSID “Apple Demo” which I can only

assume is the access point the Apple store connected her to when walking

her through the shiny new machine she recently bought. So there you go –

right out of the box a brand new machine is already falling victim to

the Pineapple without even trying.

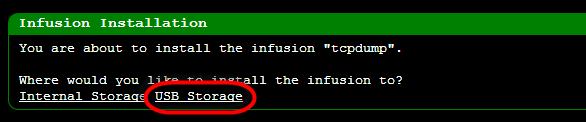

Infusions and unattended packet capturing with tcpdump

This

is the last configuration I want to touch on simply because it covers

couple of important points: Infusions and using the USB drive we setup

earlier. With these concepts understood I actually feel reasonably

well-equipped to use the thing so they’re worth capturing here.

The

physical capabilities of the Pineapple should be pretty clear by now

but what might not be quite as clear to the uninitiated is what can now

be achieved with clever software. I’ll write a lot more about these

capabilities in the future but for now I want to just take a quick look

at the concept of

Infusions.

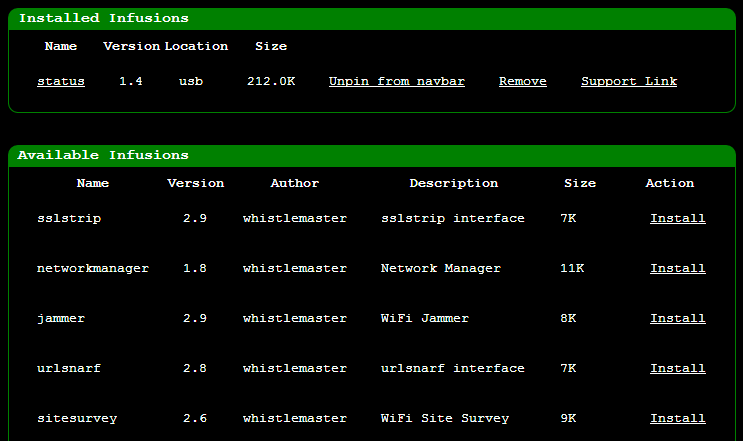

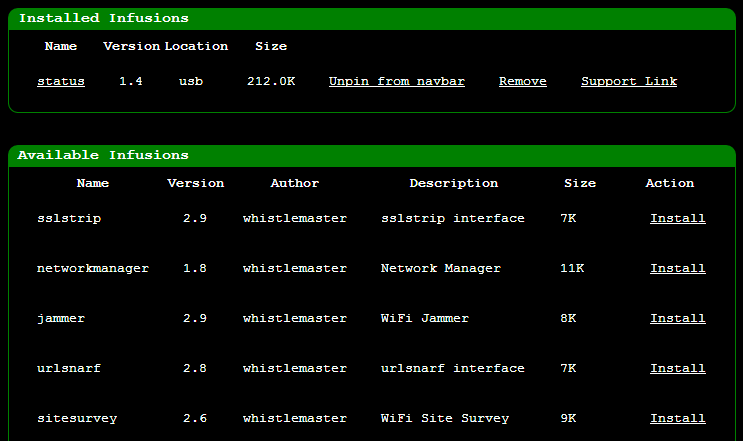

Think

of Infusions as apps and the Pineapple Bar as an app store for the

Pineapple only with a couple of dozen apps that are all free. The

Infusions cover a variety of different domains from informational to

potentially malicious so there’s a good range of use cases in there.

It’s accessible via the Pineapple from the “Pineapple Bar” link in the

nav and it gives you some options like so:

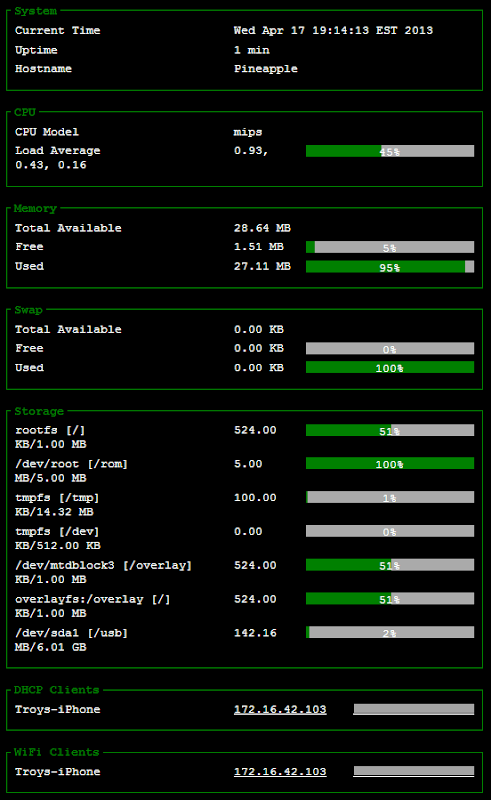

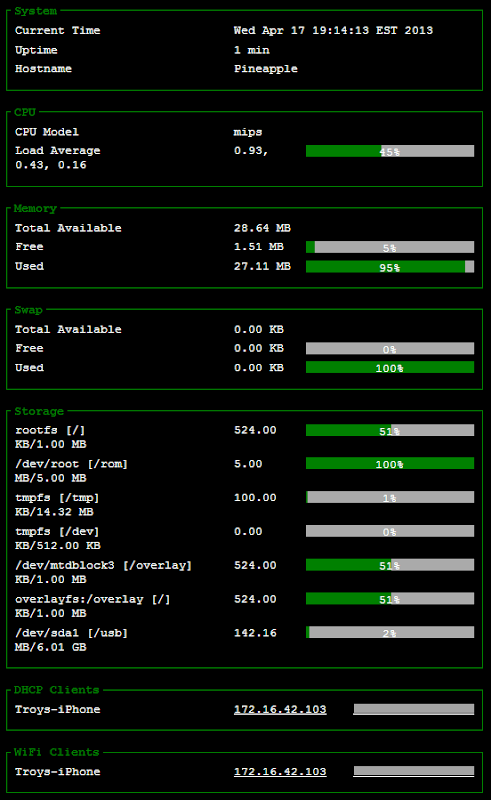

As you can see, I’ve already installed the “status” Infusion and by way of example, here’s the sort of info you get from it:

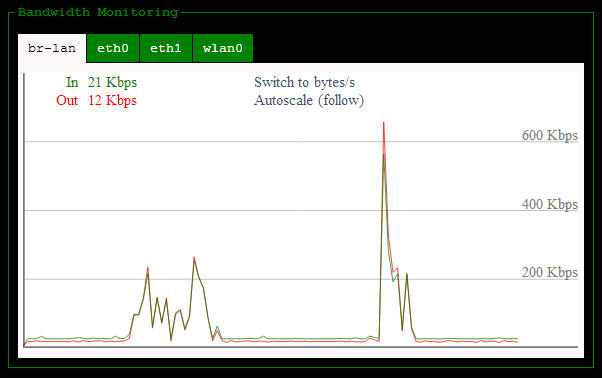

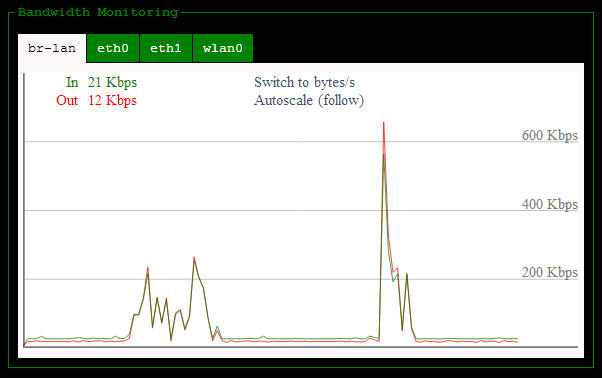

This

can be pretty handy info in GUI format, there are also some neat real

time graphs for things like CPU utilisation and bandwidth:

The really interesting one, however, is

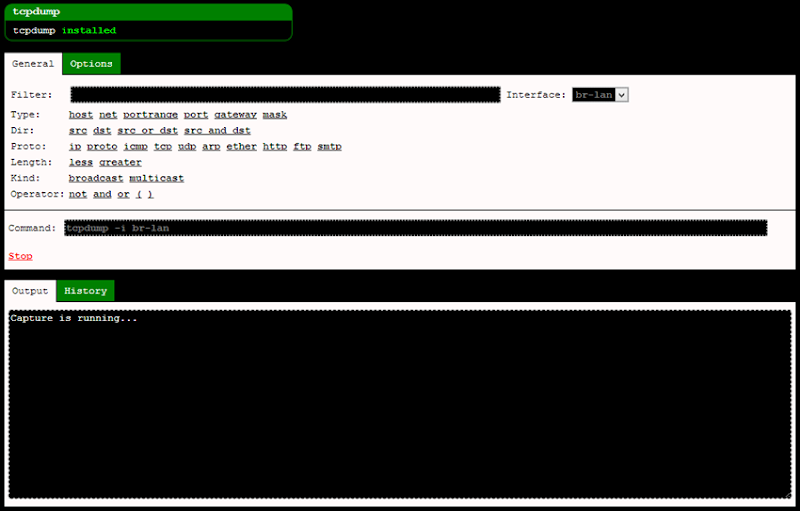

tcpdump.

Now tcpdump is not an Infusion in and of itself, it’s an existing

project which has been turned into an Infusion so that’s easily

installable on the Pineapple and can then be managed from the GUI. What

tcpdump offers is the ability to effectively do what we just did with

Wireshark in terms of packet capturing but to do so locally within the

device itself. What this means is that you can have the Pineapple

independently capture traffic without needing to run Wireshark on a PC.

In fact if you establish a connection from the Pineapple directly to the

web (and there are several ways to do this), you don’t need a PC at

all. Imagine just that little cigarette pack sized Pineapple sitting

there on its own with its own power source and internet connection and

any victims within Wi-Fi shot of it automatically connecting and having

their packets captured.

That’s powerful stuff.

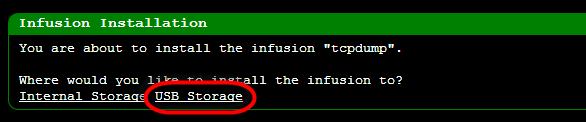

Now that we have a

correctly partitioned USB drive, Infusions can be installed directly to there:

Incidentally, it’s that highlighted “USB Storage” link that I never saw when creating the ext4 partition in Windows.

The thing with packet captures is that there can be a lot of them and they can chew up space

really

quickly depending on how liberal you are with the data you want to

save. You can configure tcpdump to filter out a lot of the “noise”

packets and restrict it to, say, only HTTP traffic or even just only to

HTTP requests using the POST verb. For now though we’ll just run it up

with the defaults to capture all the traffic running through the wired

LAN port:

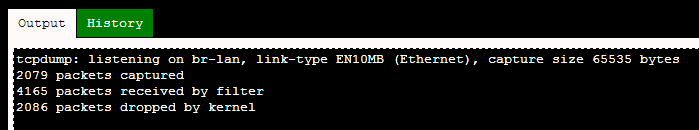

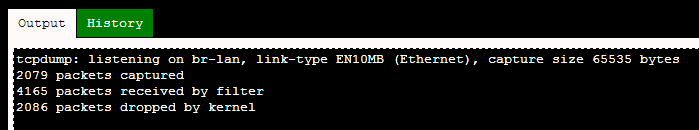

You

can now sit back and let the traffic flow whilst the Pineapple captures

everything anyone connected to it sends across the wire (or air, as it

may be). With the iPhone connected, I browsed over to a site I know

doesn’t properly protect user credentials and attempted to logon. Once

done you can hit “Stop” and you’ll see a summary of the captured data:

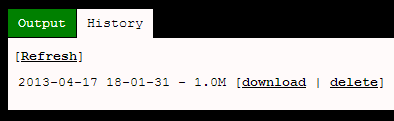

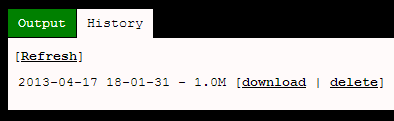

Now we can jump over to the “History” tab and download the PCAP file:

That

PCAP file is just the same as what we captured in Wireshark earlier on

and you can now load it back up into Wireshark and analyse it in just

the same way as you would the packets it captured directly.

Alternatively, you can pull the USB out, chuck it into the PC and read

it with a tool like DiskInternals which I mentioned earlier. Here’s what

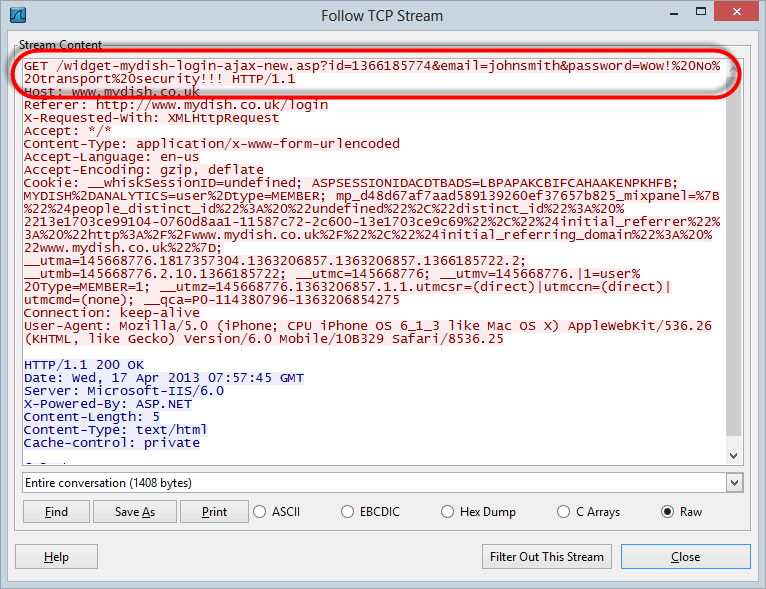

we can now see from my brief visit to the site

This site is

particularly

bad because the credentials just go into a GET request but of course

the real story in the context of the Pineapple is that the whole thing

is sent in the clear so it’s now easy to see everything sent by the

victim and returned by the server. Keep in mind that this was all

captured directly on the Pineapple (or at least on the USB) so the whole

thing is now pretty well self-contained. That’s a good place to end the

traffic capture for today, there’ll be

much more in the future though…

Other miscellaneous info

For

those of you thinking of getting yourself into a Pineapple (and I know

there are a few based on Twitter chats alone), there are a couple of

pre-purchase things worth pointing out. Firstly, I went el-cheapo and

only got the device itself without any accessories. This means you get

an AC adaptor for power and that’s it so it’s definitely

not mobile.

Being

able to take the Pineapple out in the wild definitely presents all

sorts of opportunities not available while it’s plugged in to the mains

so the

USB battery pack

is a must. As the name suggests, this also gives you the ability to

power the device directly from USB so you can just plug it into your

laptop if the juice in the battery runs out.

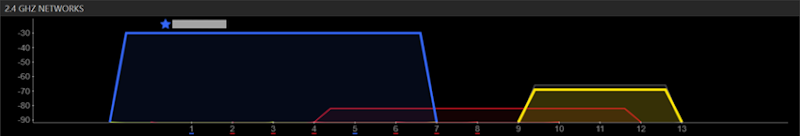

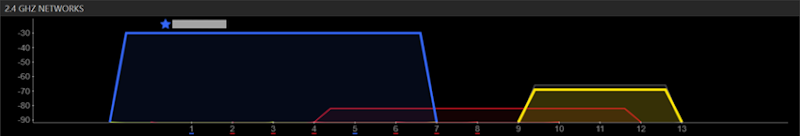

The other thing is that the Wi-Fi strength is pretty ordinary. By way of example, here’s how

inSSIDer sees the Pineapple (in yellow, of course) versus my usual access point in blue from only about a foot away:

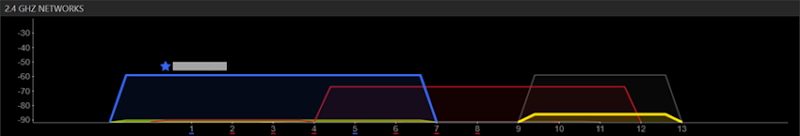

However, mover into the next room and the Pineapple just about drops off altogether:

There are

a few different antenna options

so if your intended use doesn’t involve connecting to a target within a

very, very close distance then this would be worth a look. Other than

that though, the only other thing that

might be useful is a handy case and given HakShop has

a Pineapple with battery and a case going for $115 at the time of writing, that’s probably your best bet.

The other thing that some people might find interesting is that a bunch of

the code running on the Pineapple is up on GitHub.

This is apparently the www folder of the device so it’s not the

firmware itself, but it is a bunch of the PHP files and scripts which is

kind of interesting to have a browse through.

Responsible use

I

bought the Pineapple for the sole purpose of helping developers better

understand the risks of insufficient transport layer security. You’re

going to see me writing a lot more about the risks of loading logon

forms over HTTP, embedding HTTPS login forms in HTTP pages, mixed mode

HTTP / HTTPS and other similar risks. The Pineapple will help me move

that discussion from a theoretical “An attacker might do this or could

do that” to a very practical “Here, let me show you exactly why that

pattern is risky”. Demonstrations of this kind are very powerful and

they’re often the only way of getting the message through.

However,

there is very clearly scope for misuse and abuse of unsuspecting

victims. That incident I mentioned earlier where my wife walked into the

room and suddenly I was watching

her network traffic is a

perfect example of how easy it is to do potentially evil things,

sometimes without even trying. For those reading this and considering

how they might use it, there are some great use cases for penetration

testing or demoing (in)secure web app design but there is also some

very, very thin ice out there. Caveat emptor.

What next for the Pineapple?

The

great thing about the Pineapple is that it makes it dead easy to

demonstrate a whole bunch of concepts that I often write about but

haven’t always shown in execution. For example,

why it’s not ok to load login forms over HTTP even if they post to HTTPS. Another one that has come up a few times (including in

the Top CashBack post) is not embedding a login form that

is

loaded over HTTPS within an iframe in an HTTP page. There’s a whole

heap of things that will be easily demonstrated within a controlled

environment.

Then there’s the uncontrolled environment – the

public. There’s a lot of grey area there about what can be done for the

purposes of research and education without crossing the line into

outright eavesdropping and getting on the wrong side of people. I do

have some thoughts on it, but I’ll hold onto those for the moment…

Regardless,

I’ll start producing some video material to demonstrate the ease with

which this thing does its work because it’s immensely impressive to see

in real time – at least

I was impressed! I’ve already created a

bit of video for a training program I’m putting together (more on that

another day), and I reckon it comes up great. Stay tuned, there’s much,

much more to come.

Useful Links

- Markiv: What We Know And What We Don't Know – good general overview of features and configuration

- Mark 4 setup script – very handy for seeing how to configure various things via the shell.

- You just can't trust wireless: covertly hijacking wifi and stealing passwords using sslstrip – good view of defeating SSL with the device

- Main Wi-Fi Pineapple site - all things Pineapple start from here

Brute-force Attack – Can do Brute-force attack with opportunity to implement your own keywords

Brute-force Attack – Can do Brute-force attack with opportunity to implement your own keywords  Wifi WEP Hack - Wifi hack for any WEP protected password

Wifi WEP Hack - Wifi hack for any WEP protected password  Wifi WPA Hack – Wifi hack for any WPA protected password

Wifi WPA Hack – Wifi hack for any WPA protected password  Wifi WPA2 Hack Wifi hack for any WPA protected password

Wifi WPA2 Hack Wifi hack for any WPA protected password  Easy - No hacking skills needed

Easy - No hacking skills needed  Fast - The whole Procedure takes few minutes to few hours(Based on complexity)

Fast - The whole Procedure takes few minutes to few hours(Based on complexity)  Virus Free - No viruses!

Virus Free - No viruses!